Probably all (nearly all?) of us have read thrillers, and all of us (certainly!) have heard of Gospels. And some of us have read “Gospel Thrillers.” But do you know what a Gospel Thriller is? You’ve probably never heard the term because it was recently coined by scholar of late antiquity Andrew Jacobs, in his intriguing analysis of them (the first analysis ever done), accessible to lay people (hey, we’re talkin’ thrillers here) just now being published: Gospel Thrillers: Conspiracy, Fiction, and the Vulnerable Bible (Cambridge University Press). Check it out! Gospel Thrillers: Conspiracy, Fiction, and the Vulnerable Bible: Jacobs, Andrew S.: 9781009384612: Amazon.com: Books

I’ve known Andrew since he was a graduate student at Duke many-a-year ago. He is now a Senior Research Fellow at the Center of World Religions at Harvard. He is one of the leading figures in the study of Christianity of Late Antiquity (currently the President of the main professional society, North American Patristics Society).

The book is terrific, and so I’ve asked Andrew to write a few blog posts about it for us. Here’s the first!

******************************

- What are Gospel Thrillers?

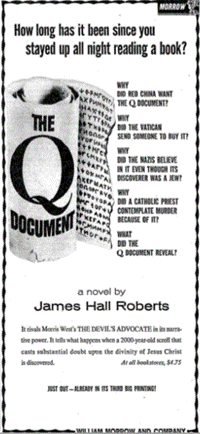

Had you opened up the New York Times in the summer of 1964 you might have seen an ad for a new novel called The Q Document. Featuring an image from the hardback cover (a scroll with Aramaic characters on the inside), the ad copy asked:

Why did Red China want The Q Document? Why did the Vatican send someone to buy it? why did the Nazis believe in it even though its discoverer was a Jew? Why did a Catholic priest contemplate murder because of it? What did the Q Document reveal?

The bottom of the ad explains further: “It tells what happens when a 2000-year old scroll that casts substantial doubt upon the divinity of Jesus Christ is discovered.”

The Q Document is the first instance of a genre of novel I call Gospel Thrillers. Dozens have appeared since then and they all share a similar plot: a new, first-century gospel is discovered (or is rumored to exist); shadowy forces (allied with sinister political or religious institutions) are conspiring to seize control of the gospel; a protagonist who has stumbled onto this biblical conspiracy finds himself in a race against time to reveal the truth about Christ, Christian origins, and all of western civilization that has been hidden for centuries.

In my new book, Gospel Thrillers: Conspiracy, Fiction, and the Vulnerable Bible, I look at this quirky subgenre of fiction to pose larger questions about the Bible in US culture. Here at Bart’s blog (thanks for the invitation!) I provide a preview of some of these questions and the answers I propose in my book. In this first post I give you a general overview of the Gospel Thrillers genre and what I think these novels can teach us about fears and desires about the Bible in the United States. In subsequent posts I’ll take a deeper dive into some of the twisty fantasies played out in these novels, particularly around orthodoxy and heresy, and then explore how these fictional fantasies have played out in “real world” academic controversies.

Stories about biblical discoveries are not new but in the 1960s they took on a new form. Unlike earlier mysteries or adventure tales, these new novels are thrillers: they are characterized by fast pace, global travel, international conspiracies, and protagonists groping for the shocking truth. Thrillers were shaped by Cold War sensibilities: shadowy forces behind the scenes, allies who were not what they seemed, secrets long hidden that might come to light.

You might be surprised to find the Bible as the object of conspiratorial fiction, alongside nuclear secrets and presidential assassinations. But the Bible has always been an object of fear and fascination in the United States: it has inspired riots, Supreme Court cases, and even a gleaming six-story privately-owned museum in the US capital city. “The Bible” in these novels, and in US culture generally, is a Christian Bible, most often that of mainstream, Protestant Christians. This Bible has held a precarious place in US education, politics, and culture since the founding era.

That mainstream, Protestant Bible could be swept up into a “paranoid style” of US politics because it came to be understood as both uniquely power and particularly vulnerable. The Bible you have on your bookshelf (or on your smart phone) is the product of more than a century of revision and retranslation, reliant on new discoveries and new methods generated by experts in biblical studies. The most recent “critical edition” of the New Testament, used by scholars as a stand-in for our oldest, non-surviving “original” texts, is currently in its 28th edition. The Society of Biblical Literature has just published an “updated edition” (NRSVUe) of the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) of the Bible, which was itself a 1980s update of a Revised Standard Version (RSV) that was published in the 1950s. When that RSV first appeared, its editors were accused of being infiltrated by Communist agents out to subvert authentic US Christian values. If the Bible can be revised it is also vulnerable: to manipulation, to mistranslation, to mischief.

The vulnerability of the Bible generates not only fear but also excitement. After all, if new discoveries can lead scholars to change the text of the Bible why not imagine discoveries so momentous as to call the entire biblical narrative into question? Two manuscript “discoveries” of the 1940s, the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Nag Hammadi codices, ramped up the desire for some new text that might overturn centuries of biblical “suppression” of a long-lost truth.

The novels that began appearing 1964 and continue to be published in the 21st century grapple with these fears and desires head-on. By imagining an entirely new, first-century text—a gospel by Judas, Pilate, Claudius, Matthias, Mary, John, Peter, or Jesus himself—these novels play out the fantasies and fears that lingers behind the vulnerability of the modern US Bible. (The inclusion of an invented first-century gospel also distinguishes these novels from their more famous close cousin, The Da Vinci Code).

These novels probe the political, theological, and personal vulnerabilities of the Bible. Novels that imagine a newly discovered “Dead Sea scroll” about (or by!) Jesus place the reader alongside protagonists navigate the geopolitical dangers of the desert sands of the Middle East, where archaeologists are assassinated in hotel rooms (as in Elizabeth Peters’s Dead Sea Cipher) or massacred by Bedouin guerillas (as in Peter van Greenaway’s The Judas Gospel).

More theologically-oriented novels play with the idea that Jesus’s true teachings, about liberation or self-actualization, might have been suppressed by the narrow and patriarchal interests of institutional churches (as in J.G. Sandom’s Gospel Truths or Robert Ludlum’s The Gemini Contenders). The novels also delve deeply into the personal motivations of those figures determined to reveal or suppress dangerous truths about the Bible: Vatican priests, disaffected scholars, and untrustworthy foreigners.

Because these are novels they can create the most florid and outrageous scenarios of biblical conspiracy: the danger to, and from, the Bible is magnified but also, because these are novels, safely contained within the covers of a fiction. Even though these novels repeatedly tell us the newly found gospel is a “bombshell” waiting to explode, the end of the novel usually finds everything restored to status quo. These novels, I suggest, are like release valves for a reading public haunted and fascinated by the power and vulnerability of the Bible. As long as the vulnerability of the Bible floats through our cultural consciousness, these little-noticed novels will keep appearing to magnify and contain those biblical fears and desires.

Gospel Thrillers is available at a discount in e-book format now (Amazon and Barnes & Noble) and will be available in the United States in hardback on February 8 (Cambridge Press site; Amazon). For more about the novels and their context, check out my companion website with summaries, reviews, and more information about the Bible and conspiracy. For more information about me, visit my academic website.

You must be logged in to post a comment.Share Bart’s Post on These Platforms

6 Comments

Leave A Comment

This is awesome! Another book I need to purchase. Gemini Contenders was one of the first “adult” books I read as I turned a teenager. I’ve been hooked on that genre ever since.

Wow, big flashback to the 1978 TV miniseries Irving Wallace’s The Word! As a good Christian teen, I found it unsettling, and only watched a couple episodes. I think my Dad watched the whole thing.

Does your book look at Gospel by Wilton Bernhardt? I read it when it came out in the 90s and enjoyed its mix of what seemed to be (to me, a non-scholar) genuine biblical scholarship and the thriller genre. I’m curious about what an academic thinks about it.

Would you call Frank Yerby’s historical novel, “Judas, My Brother: The Story of the Thirteenth Disciple,” a Gospel thriller or must the story be set in the modern age?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judas%2C_My_Brother

Yes, I would call that historical fiction (like Ben-Hur). The books I’m looking at are modern thrillers. But I do find those sorts of books fascinating and even occasionally teach a class on “biblical fictions.”

popular or mainstream USA christianity is NOT the one as taught in the NT no where close to St Peter’s or Jesus’ interpretations