In my two previous posts I’ve been trying to explain that the historical-critical view of the Gospels, in which they are recognized not always to represent historically accurate information about Jesus, is not necessarily a view that “trashes” them. Instead, it is a view that tries to understand what they really are instead of insisting that they are something else. Accepting them for what they are is surely a good thing; making them into something they are not can’t be good.

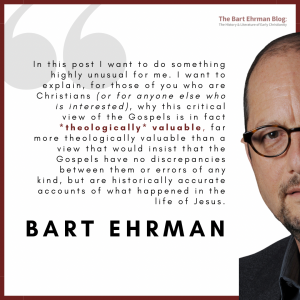

In this post I want to do something highly unusual for me. I want to explain, for those of you who are Christians (or for anyone else who is interested), why this critical view of the Gospels is in fact *theologically* valuable, far more theologically valuable than a view that would insist that the Gospels have no discrepancies between them or errors of any kind, but are historically accurate accounts of what happened in the life of Jesus.

When I was a Christian, once I came to the conclusion that the Gospels in fact are full of contradictions and discrepancies and historical inaccuracies– after many years of research – I also came to realize that this understanding was remarkably fruitful from a theological point of view.

If Mark and Luke, for example, have different ways of telling the same story, then they each want to emphasize and teach something that is different (not the same). The discrepancies tell you what each one wants to teach. If you’re not a fundamentalist who cares only that the Gospels are historically accurate, and if you have any literary sensitivity at all, if you have any sense that “what really happened” is not the only or even the most important thing, if you have any grasp on the reality that great literature can teach important lessons (even if it contains material that didn’t happen) – then recognizing what each Gospel is trying to teach enables you to embrace the message of each Gospel without pretending that it’s the same message as every other Gospel. Not to do this is to impoverish the teachings of the Gospels, each and every one of them. (Now that I think of it – that’s true even if you’re not a Christian. These are great books, and their authors deserve to be heard and understood and considered as giving important understandings of the world, and about Jesus, and about ultimate reality.)

For example, in Jesus Interrupted I give a detailed analysis of the story of Jesus going to his crucifixion in Mark and in Luke. The reality is that these two versions of Jesus in the face of death are very, very different. In Mark, Jesus appears to be in shock. He says nothing the entire time – while en route, while being nailed to the cross, while hanging on the cross, until the very end, when he cries out the gripping words of Psalm 22 “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Many many people have written me to point out that the Psalm Jesus quotes *ends* by the Psalmist acknowledging God’s presence in his life and expressing a hope that God will resolve his difficulties, and have argued – this is a very old and standard argument – that Mark means for us to think of the *end* of the Psalm when Jesus quotes the *beginning*. I think this is completely wrong. In fact, I think it is the opposite of being right. Mark’s Jesus does not quote the end that is a word of comfort; he quotes the beginning which is a word of despair. Because for Mark, Jesus is in despair. He has been betrayed and denied; his followers have not stood up for him but have fled; he has been ridiculed by the Jewish authorities, the Roman soldiers, people passing by the cross; an even by both criminals. In the end he dies feeling forsaken of God.

Luke portrays Jesus very differently indeed. Here Jesus comforts the weeping women while en route to crucified; he prays while being nailed that God will forgive those doing this to him; he talks to one of the others being crucified and assuring him that together they will, that day, wake up in paradise, and in the end, *instead* of asking God why he has been forsaken, he confidently entrusts his spirit to his loving Father. Jesus here – radically unlike Mark – is calm and in control and knows that God is on his side to the very end.

The problem is when people take the version in Mark, and then the version in Luke, and combine them together into one big mega-Gospel in which BOTH are taken as “what really happened.” But my view is that you really should not do that. Because when you do, you change what *both* authors have tried to say and you destroy how *each* of them portrayed Jesus going to his death. By doing this, you have in fact written your own Gospel. Which is fine, if what you want to do is write a Gospel. But if you want to know what Mark is trying to say, you can’t do it by pretending that he’s saying the same thing as Luke. And vice versa.

Of course, when you throw both Matthew and John into the mix, each with their own distinctive portrayals, then you have a real mess – a very big Gospel in which Jesus says and does everything found in each one. That’s how you end up with the so-called “Seven last words of the dying Jesus.” These seven last sayings are the ones found in Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John when you combine them. But the attitudes and understandings of each of these sayings actually make sense only in their individual Gospels, not when you combine them together. So once more you have robbed each author of his integrity.

In my next post I’ll explain why it is theologically useful to let Mark have his own say, and Luke his, in this particular story. I myself am not championing either theology – since I’m not a believer. But I think each message is terrifically powerful, and worth listening to, without adulterating it by making both of them say basically the same thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.Share Bart’s Post on These Platforms

9 Comments

Leave A Comment

Thanks, Bart, for your insight into the gospels and the entire New Testament. I would think that understanding and accepting that each gospel writer had his own view and message would take the pressure off fundamentalists who feel as if the must, somehow, “make” the gospels seem as if they are in total agreement. As a former evangelical and a current *still trying to figure that out*, I am enjoying your blog, and your books and online courses have become my go-to in the last year or so. I think it’s very beneficial for scholars, in any discipline, to write articles/books designed for laypeople. Thank you!

A very special post for those of us who are believers! Thank you, Professor Ehrman.

Professor Ehrman. If I understand this correctly Leviticus 17:10 forbids Jews from consuming blood, “If any man of the house of Israel or of the strangers that sojourn among them eats any blood, I will set my face against that person who eats blood, and will cut him off from among his people.” In John 6:54 Jesus says, “he who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day.” Jesus was a Jew telling other Jews to drink his blood. Do you think it is likely or not that Jesus would have said this?

I think it’s incredibly unlikely. The passage is reflecting the later Christian practice of the Lord’s Supper, where “his blood” is symbolically presented in the cup of wine. Only later did theologians argue that the wine actually became his blood. But Jesus almost certainly did not talk about the need to consume his body and blood: the traditions about the Lord’s supper came only after his death.

One thing I keep thinking about is that several of the earliest surviving Gospel manuscripts (P52 and P90) are from the gospel of John, and that they are both part of John’s passion narrative. Is there a possibility that these were not written as part of the fourth gospel as we have it today, but that they were from an earlier source, possibly containing only the passion narrative, that canonical John would go on to use? It seems to me that there is a “hybrid” character to John and it would make sense if it collected and edited together existing documents. Am I off base there?

It’s *possible* — but one would need to find sime reason to think so, especially since the wording in the fragments is so very similar to that in the later mss. I can’t think of an argument for the idea, but it’s not impossible.

Here’s what I have to ask:

1. The belief is that St.Thomas was the disciple who converted Hindus(that is an assumption) in the South Indian state of Kerala. Syrian Christians is the name given to these Christians because their liturgy is/was Syriac.

2. Are you aware of the spread of Christianity to this region, and is there any real concrete proof that it was the apostle Thomas who brought Christianity to this region of the world. In fact if I recall correctly, according to oral tradition, there was supposedly a stop in Persia during the time of Darius(?) and a coin was minted in Thomas’s honor. But to continue, from there Thomas sails down to the coast of Kerala and converts some of the brahmin caste there, though given the fact that there supposedly 6-7 million Syrian Christians in various denominations, it is really unlikely that it was only brahmins who were converted.

Could you please enlighten us on this topic, a very specific response to the whole St Thomas Christians was posed on my brother Thomas Joseph’s blog, which if you wish I can share.

Thank you for all that you have contributed to the Epistemology of Christian history.

The tradition that Thomas brought Xty to India goes back to the third-cnetury legendary account known as the Acts of Thomas. That’s our oldest account and it is indeed highly legendary –but a terrificallyfasicnating account. There is no indication from any time earlier, no historical record to suggest the story is true. And the stories of the account itself (as you’ll see by reading it) are entertaining rather than biographical.

I find your way of telling the “apparent truth of the gospels” from so many perspectives quite refreshing. It took a couple of years of study for me to find a some what balanced perspective which allowed me to stay Catholic but still embrace a critical and scientific way of reading the gospels. The odd times (Covid19 etc.) of the last three or so years gave me a new way of looking at biblical reality. In my studies I found that in several Papal bulls (Pope Leo the 13th., Pope Pius 11 and Pope Paul 6th.

and Pope Paul) the pope tells Catholics they may read the OT/NT from a critical perspective and that such reading and rereading of the gospels is very useful to the faith. He also growled and informed us believers that anyone tampering with Holy Scriptures by altering the text would find themselves sleeping in the barn.