Now here are some conversations between Jesus and one of his women followers I bet you’ve never seen before!

When Salome asked, “How long will death prevail?” the Lord replied “For as long as you women bear children.” But he did not say this because life is evil or the creation wicked; instead he was teaching the natural succession of things; for everything degenerates after coming into being. (Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies, 3, 45, 3)

Why do those who adhere more to everything other than the true gospel rule not cite the following words spoken to Salome? For when she said, “Then I have done well not to bear children” (supposing that it was not necessary to give birth), the Lord responded, “Eat every herb, but not the one that is bitter.” (Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies, 3, 66, 1-2)

And when the Savior said to Salome, “Death will last as long as women give birth,” he was not denigrating birth — since it is, after all, necessary for the salvation of those who believe. (Clement of Alexandria, Excerpts from Theodotus 67, 2)

These snippets are taken from the long-lost Gospel of the Egyptians, known to us only because it is quoted six times by the late-second century church father, Clement of Alexandria (that is, we don’t have a manuscript of the Gospel itself). These quotations are my translations from The Other Gospels: Accounts of Jesus from Outside the New Testament, edited and translated by, well, me and my colleague Zlatko Pleše (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

If you want to see full translations and introductions to this non-canonical Gospel — and to about 40 others! – that’s a good place to turn.

But for now: who is this woman disciple named Salome, and what is the Gospel of the Egyptians? Here’s how I explain it all in our book (pp. 115-17; slightly edited here).

*****************************

Only Clement quotes the book, six times altogether. On two occasions (sayings 2 and 5) he mentions the Gospel by name: in both instances it involves a conversation between Jesus and a woman disciple named Salome, who Salome is known to us from two passages in the New Testament (Mark 15:40; 16:1 and several non-canonical texts). In four other instances, Clement cites Gospel quotations of a conversation between these two; by inference, these quotations are also generally understood as having come from the Gospel according to the Egyptians. All these quotations deal with the same basic issues: sexual abstinence, the relation of the genders, and the legitimacy of childbearing.

None of Clement’s quotations of the Gospel is disparaging; on the contrary, he appears to hold it as an authority. But he does assert that the teachings of the Gospel have been twisted by those who take them in a literal way to denigrate sexual activities and procreation. Clement quotes the Gospel in order to provide his own allegorizing interpretation of it. A more straightforward reading of the Gospel suggests that it was indeed written to support an ascetic lifestyle that rejected the pleasures of sex and denied the value of procreation. Its views appear to be based on a close reading of the Adam and Eve stories of Genesis 2-3, where, for example, pain in childbirth is seen as a direct result of sin having entered into the world.

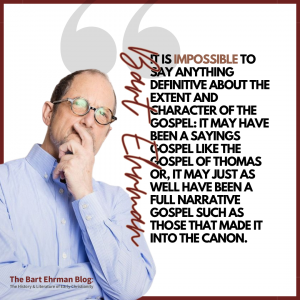

It is impossible to say anything definitive about the extent and character of the Gospel: it may have been a sayings Gospel like the Gospel of Thomas or, it may just as well have been a full narrative Gospel such as those that made it into the canon. If the latter, there is no trace in any of our sources of the rest of the Gospel, just the conversation(s) Jesus had with Salome, presumably, but not necessarily, during his earthly ministry (it is also possible that it consisted of conversations from after the resurrection).

Some scholars of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were keen to tie this Gospel to other, equally scarcely known documents: the Gospel of Peter; sayings of Oxyrhnchus papyri 1 and 655 (which are now known to have come from the Gospel of Thomas); the Gospel of the Hebrews; the apocryphal Epistle of Titus; the Strasbourg Coptic fragment (see later in the collection) and so on. The reality, though, is that we simply do not have evidence to make any of these suggestions plausible.

There have long been debates concerning the name of the Gospel, and of what the name might signify. W. Bauer maintained that it was the Gospel used by gentiles in Egypt, and that it was called the Gospel according to the Egyptians to differentiate it from the other Gospel widely in use there, but by Jews, the Gospel of the Hebrews (Orthodoxy and Heresy, p. 50). Other scholars have seen this reasoning as faulty, since Jews also could be Egyptian, and there were other Gospels (many other Gospels!) in use by Christians (Jew and Gentile) in Egypt. More likely is the view that the title was devised by non-Egyptians to designate a Gospel used by the Christians of Egypt.

The Gospel must date before the earliest known references to it, that is, prior to the writings of Clement of Alexandria in the late second century. Most scholars date it to around the middle of the century. Given its title and its early attestation by the Alexandrian church fathers Clement and Origen, it is widely assumed to have been written there, in Egypt. There is now another Gospel called “according to the Egyptians,” in the Nag Hammadi Library. These two books have nothing in common and are not to be confused with one another.

Here are some other places you can find brief discussions of this now-lost Gospel.

Bibliography

Bauer, Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity. (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1971; German original 1934).

Elliott, J. K. The Apocryphal New Testament. Oxford: Clarendon, 1993; pp. 16-19.

Klauck, Hans-Josef. Apocryphal Gospels: An Introduction. London: T&T Clark, 2003; German original Stuttgart, 2002; pp. 55-59.

Schneemelcher, Wilhelm, “The Gospel of the Egyptians” in New Testament Apocrypha, ed. Wilhelm Schneemelcher; tr. R. McL. Wilson. Louisville: Westminster/John Knox, 1991. Vol. 1, pp. 209-15.

You must be logged in to post a comment.Share Bart’s Post on These Platforms

20 Comments

Leave A Comment

Hello, Bart. Clement seems to specialize in quoting otherwise unattested works. Isn’t he also our only source for the controversial Secret Gospel of Mark?

It depends on whether the letter allegedly written by that was “discovered” by MOrton Smith was actually written by him. I don’t think so myself.

Dr. Ehmran, I must say you look great in this Facebook post. Who ever your photographer is, great job! The blue look amazing on you.

https://www.facebook.com/joey.luna.92505?mibextid=ZbWKwL

Hi Bart! We just watched one of your lectures on YouTube and really enjoy listening to you. Just have a question.

There is a new documentary called Christpiracy which examines the Gospel of the Ebionites with possible early writings that say that John the Baptist and James followed a vegetarian diet. I imagine that you haven’t had a chance to watch it, since it hasn’t been released in streaming yet. I think it may eventually be on YouTube. It was just in the theaters, but is gone now.

I have read somewhere that James, the brother of Jesus refused to wear wool as well. There are some quotes from the gospel of the Ebionites that say that Jesus had no desire to eat the Passover lamb with them. There are other writings that suggest Jesus cared for animals. There are even fixed mistranslations that suggest that the cleansing of the temple was primarily anger at the violence and slaughter of animals, not greed .

So my primary question is: Why exactly were the Ebionites vegetarian?

Did they know something we don’t that was lost to history or destroyed? Or was it due to the destruction of the temple?

Thank you,

Deb Sahd

Lancaster, PA

I talk about this a bit on the blog (and recently I think). If you do a word search for “Ebionites” you’ll see. Our sources do indicate they were vegetarian, and there are debages about why. Here are a couple of good options: (a) some Jews in antiqutiy were vegetarian becuase meat was largely available only when it had been sacrificed ot pagan gods, and eatin it might be seen as an act of participation in pagan religoius practices; (b) Jewish followers of Jesus thought that he was the ultimate sacrifice, and so killing animals, which was normally done in a religous context as a sacrifice, wsa no longer to be practiced. The reality is that we have very *little* from Ebionite sources (the Gospel of the Ebionites is lost; we have it only in quotations of the 4th century church father Epiphanius, who opposed them), so it’s very hard to know what they thought/said/did — and it may well be that there were various groups of them with various views and practices.

Clement’s first rationalization has a bit of a Buddhist flavor to it, as does Jesus’ last saying; birth and death being inextricably linked in a never ending cycle. I always have to be careful to not let my Buddhist conception of death (and other things) cloud my readings of early Christian texts. It is interesting how intertwined death and sin are in some early Christianities. And here we have childbirth in the mix.

Thank you for the distinction between the two Gospels. I erroneously assumed at the outset that you were referencing the Nag Hammadi text.

Hi bart

I heard that a resent study named “The hands

that wrote the bible” carbon dated 11-12 daniel in qumran from 180bc-170bc but i think there have been lingistic studies/carbon daitings on the manuscribbes found in qumran. The oldest date on the 10-11 was ~130bc. I think the short period is normal because the dead sea scrolls writters intressted in just that kind of text, also The book of Daniel was probably war propaganda.

But what to you think about the study did it get the carbon daiting wrong?

I’m afraid carbon dating can’t date a piece of organic material with that kind of accuracy. So either someone’s makin’ stuff up or misunderstands what others have shown. In any event, it’s clear from literary evidence that Daniel was written in the 160s BCE.

Hi,

1) Is the today’ Christian marriage ceremonies biblical? I couldn’t find information regarding it, other than that they were arranged contracts. In this line of proof, could we say that the civil marriage contract (without the religious act) is as biblical as having been united by a pastor?

2) Do you think some people don’t want to have an open mind regarding other possibilities regarding the text because of fear? How can one help them?

1. I don’t think there’s just one kind of Christian marriage ceremony; but the Bible gives no instructions for one in any event.

2. Yes indeed. We can help by studying the texts diligently, learning the truth about them, and speaking the truth with love and conviction.

Hi Bart

The fragments of The book of Daniel have been lingisticly dated, but have they been carbon dated?

How precise is carbon daiting and how precise is lingistic daiting?

Not that I know of. The literary evidence is quite compelling.

Could the Gospel of the Egyptians be related to the Coptic Church? Or does the Coptic Church go back that far?

Technically the Coptic church is later, but if this Gospel did go back to Christianity in the 2nd c. in Egypt, the Chrisgtians who produced and used it would have been the predecessor in some sense of hte 4th-5th c. Coptic church. This Gospel, though, was Greek, written for Greek Christians, not those speaking Egyptian.

These extant and apocryphal gospels present such a wide range of beliefs and Jesus perspectives. Have you considered a book that presents the spectrum? There are probably some consistencies, certainly inconsistencies, time frame progression from first century through fourth century.

I read and enjoyed your book “Lost Christianities”. Certainly a new book regarding such documents would include some of the Lost Christianities content, but would be so much more and a great central reference source.

Ah, well, Lost Christianities does try to present the spectrum, from Ebionites to Marcionites to Gnostics to Proto-orthodox. But obvoiusly a whole lot more could be said. I guess most of my career has been spent saying it in various ways. But I’m not going to be devoting a major reference work to it. There are books like that out there though. A good place to start is with Walter Bauer’s Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earlies tChristinity.

Professor Ehrman,

I would like to read a book about the formation of the NT Canon, but I’m nervous Professor Metzger’s is too big a place to start. It’s it accessible, or would you recommend something else?

Ray

You might start with Harry Gamble’s book The New Testament Canon: It’s Making and meaning.

Dr.Ehrman. I have some questions about the salvation theology.

1.Why Jesus’ Death can bring salvation? I mean, it is very weird: Another person’s death can give you salvation. And if it brings me salvation, then I can do bad things openly?(even if I kill a child, I can still get salvation! ). My sense is that the followers didn’t understand why “Messiah” would die in such a lowly way, so they came up the weird idea.

2.What does salvation mean? It certainly does not mean something about this life, because people still suffer in this life. so I guess Either it mean allowed to enter the Kingdom of God when the end come OR going to heaven immediately after death. (In both ways , it means eternal life in “heaven”). Am I right?

Thank you very much!

1. Salvation of course is a doctrine understood differently by different people; there’s not a single view. Most Christians historeically, though, would say that Jesus’ death was an atoning sacrifice that paid for your sins, and if you accept what he has done for you you will strive to live in ways pleasing to him. If you decide not to, then you have decided not to be his follower after all.

2. Originally “salvation” in the Christian tradition mean not being destroyed on the coming Day of Judgment, but being delivered from that; it soon came to mean going to heaven and being saved from the torments of hell.